— Log in to watch the artist video if you have been given an access

- Artist

- Marcos Ávila Forero

- Title

- Un pechiche para Benkos

- Year

- 2016

- Duration

- 5 min 28 s

- Format & Technical

Single channel, HD video, colour, sound

5 + 1 AP

- Music

- Text

- Special thanks

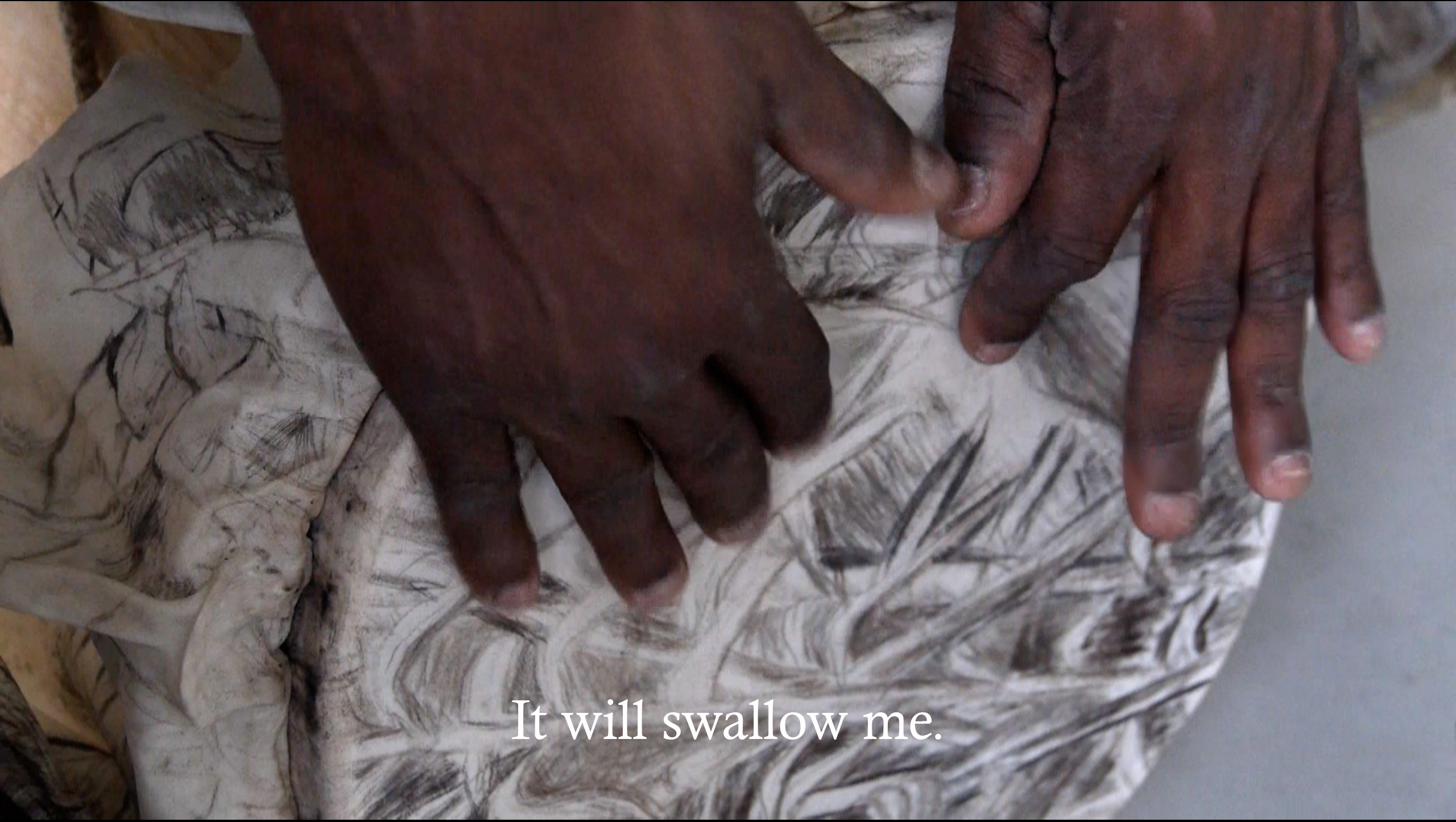

The pechiche, an ancient kettledrum, is inscribed in the history of Latin America’s colonization and the history of slavery. It was traditionally used as a means of communication in the colonies, especially as a warning system. For Un pechiche para Benkos (A pechiche for Benkos), Marcos Ávila Forero commissioned the creation of a pechiche to a group of Colombian artisans whose task revolves around conserving and recreating objects used in the colonies. The artisans, who had never created a drum before, worked with raw materials and applied the technique used in the navigation industry: handmade ropes, chopped wood and parchment-like leather. In order to have the drum played as tradition dictates, Ávila contacted the Congolese ethnologist, musicologist and percussionist Émile Biayenda, specialized in slavery and colonial history in Latin America, whose playing hands appear in the film. Ávila asked Biayenda to retell, through his drum tapping, a story through the same codes and messaging system of the ancient times.

Un pechiche para Benkos explores the video format as a way of escaping from the commodification of both art and the object. It also uses the medium as a text, a platform to produce different historiographic accounts in a place where both postcolonialism and neo-imperialism coexist, Colombia. Those narratives, which challenge the Western hegemonic discourse, are aided by an inner exploration of the technological medium they unfold in. The video format allows for this multiplicity of voices to dialogue in the same space and time, though belonging to different eras, yet in a realistic manner; thus challenging the limits of representation. This dialogue, impossible otherwise in an real context, also serves to illustrate the complexity of opposition within postcolonial societies, using different apparatuses that allow for a polyphony and exchange of experiences. Ávila’s artistic practice, based on critical investigation, uses new media as a way to link himself to the collectivity of the environment he works in, opening alternative processes of power negotiation and transmission.

The film’s story incarnates two characters at the same time. On the one hand, a clandestine modern migrant, Camara Mwa Abdallaye, hidden in a cayuco –a fishing boat– trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea. On the other hand, Benkos Biohó, dead in 1622, a runaway slave, leader of the first Colombian emancipation movement, chained in a slave ship. Though it appears the words talk about music, soon we realize they talk about the boats’ framings. Said Abdallaye that, inside the boat, in quietude, the sound of the waves crashing transformed the boat into an enormous sound box; the sound that Biayenda’s tapping recreates. The strength of the pechiche is, precisely, to place its audience in a trance through the incessant tapping, and tell a story. In the stream where the self and the other dissolve in time and space, memory embraces us at the hypnotic sound of ten fingers.

Carlota Surós

Stills