— Log in to watch the artist video if you have been given an access

- Artist

- Marcos Ávila Forero

- Title

- June 28th 1950, The Agrarian reform

- Year

- 2017

- Format & Technical

Double channel, HD video, colour, sound

Edition of 5 + 2 AP

- Produced by

- Photography

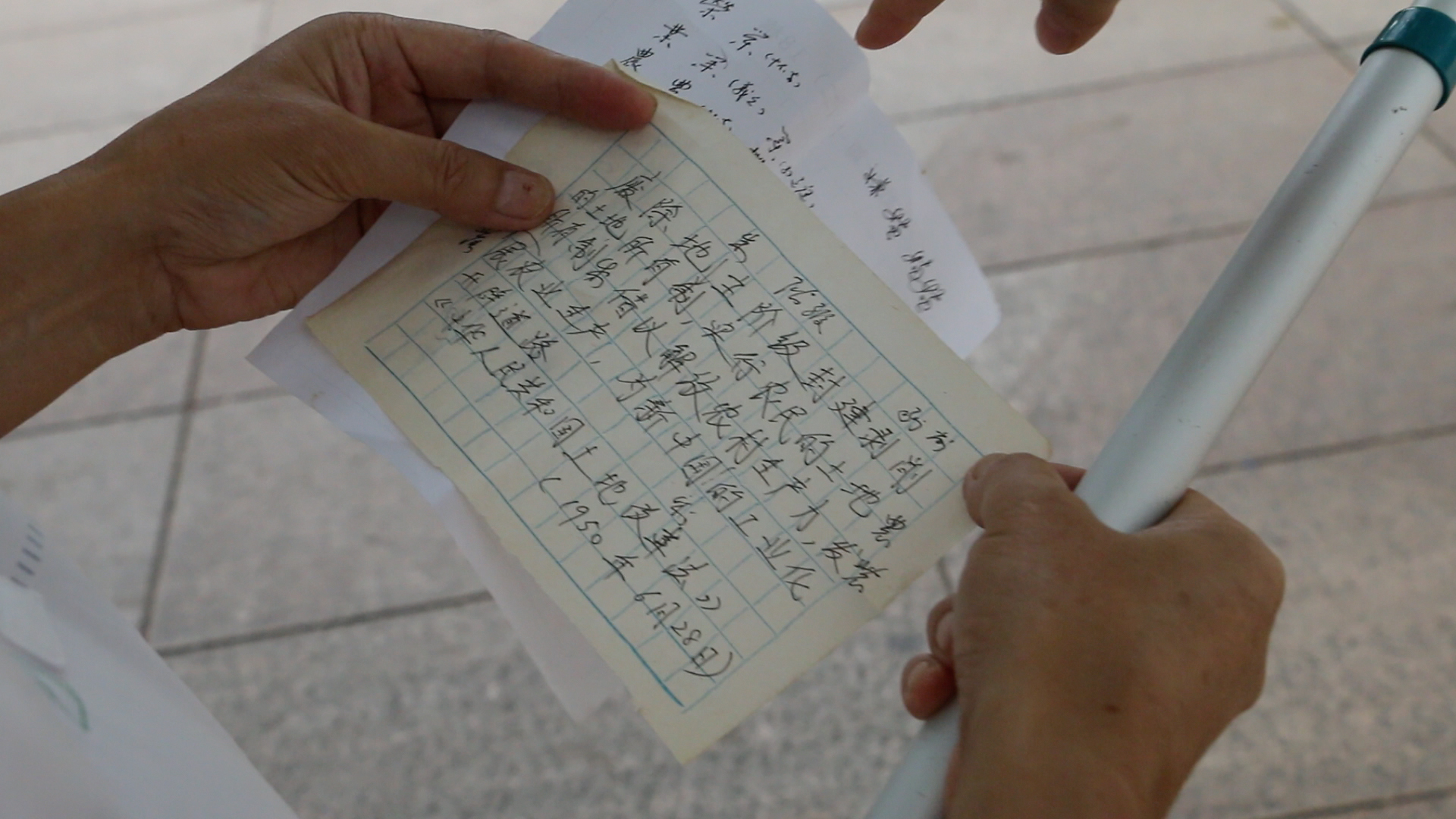

For the piece June 28th 1950, The Agrarian reform, the artist requested a Chinese calligrapher specialised in italicised form, to work on this millennial technic of popular calligraphy —that it is done using water directly on the ground. This form, also called “grass script” or “cao style”, is used to write drafts but also more artistic text, being the one Mao Tse Tung chose for the transcription of his poems. For Avila´s work, the text transcribe the content of the agrarian reform after de Chinese Revolution with the water of the Yangtze River. The Agrarian Reform of 1950 was decisive in the formation of modern socio-economics in the Chinese post-Revolutionary agricultural community, since for centuries, the country had been based on the concentration of land ownership, the exploitation of the peasantry, and inequality in wealth and political power.

Chinese calligraphy, also known as shūfǎ, is an ancient practice that carries multiple meanings. On the one hand, it is the purely aesthetic act of writing; at the same time, it may be understood as the set of features that characterise the way in which a person writes, or in which a document is written. In its italicised form, or cǎo, it is an art wherein abstract expression takes precedence over legibility. Likewise, in its technique the action itself takes precedence over its transcendence. The sun evaporates the letters on the earth in just a few minutes, and upon disappearing, explains Ávila Forero, the written texts become a “secret assertion”. The ephemeral nature of this practice, for which a permanent materialisation cannot exist, creates in it an invocation: continually vanishing transforms it into a utopian act.

Marcos Ávila Forero’s multidisciplinary production focuses on critically investigating cultural, ideological, and social contradictions. He works with collective and individual histories, forgotten rituals and memories, with the stories that have been left out of the hegemonic discourse of History. The use of materials and techniques belonging to the contexts in which he works, as well as collaboration with local figures and collectives, make his actions particularly interesting in terms of transmission and translation. Given its cultural, social, and historical particularities, together with its legacy of communist ideology as well as a position of immense international political pressure, the Chinese experience has become a symbol for so-called third world countries. This reform, still in force today, is at the core of the peasantry’s current demands and vindications not only in China, but also all across the Global South. Registering the text with water momentarily reveals a fleeting yet enduring vestige of a struggle, a memory, and a latent history that are, like other traces, destined to be re-written again and again as an act of resistance.

Antonella Medici

Stills