Chip Lord in conversation with Steve Seid

— BURNT OFFERINGS: Ant Farm and Media Burn

Friday 26 May 2017, 12:30 — 1:45 pm

…In the words of Steve Seid

Some works of art are like rehearsals for the future—provisional try-outs for possibilities glimpsed, but certainly not realized. Other works take a different tack, speculating on cultural trajectories whose rising arc is observed, but whose terminus is never quite calculated. Ant Farm’s Media Burn (1975) illustrates a middle road, the future glimpsed but the magnitude of that prognostication never imagined.

Staged in a parking lot in San Francisco on July 4, 1975, Media Burn—a performance, a videotape, and untethered photographic images—gathers its critical strength from a complex amalgam of signifiers, intuitively felt through their monumental familiarity. The performance was also wrapped in an ironic patriotism—after all, it was Independence Day and the red, white, and blue bunting was everywhere.

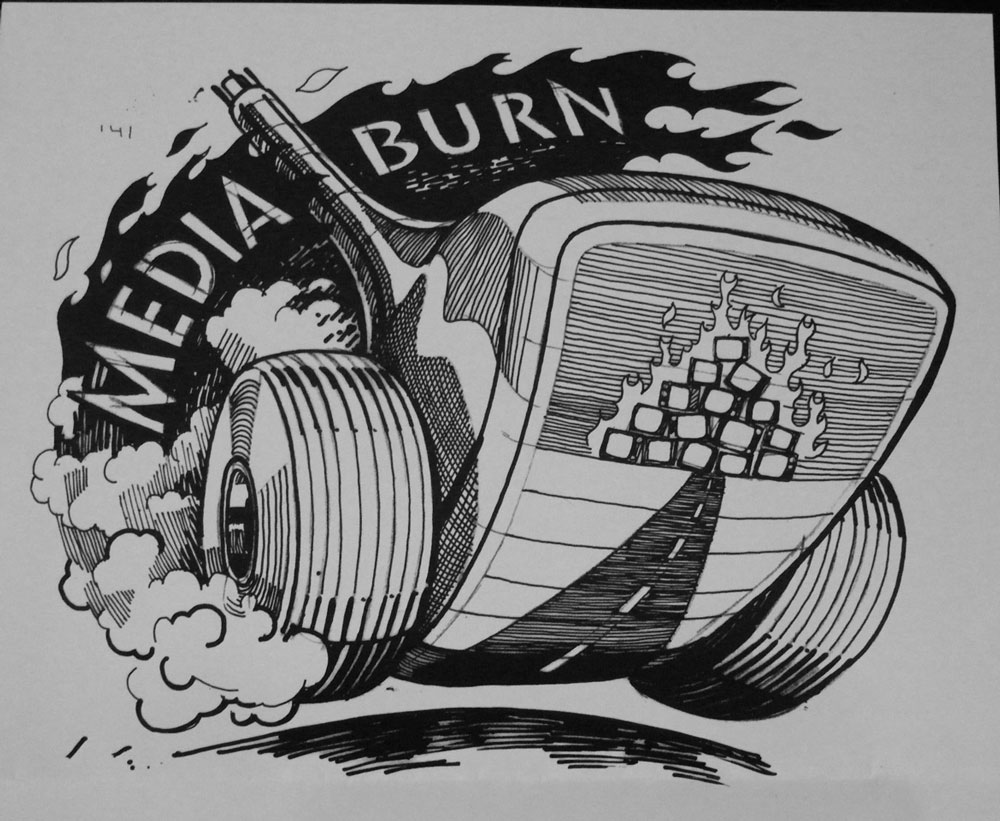

A surface reading of this surprisingly ambitious assembly comes up with a simple incendiary media bashing. A customized 1959 Cadillac Eldorado, posing as an earthbound rocket, collides at forty-some miles/hour with a pyramid of about forty television sets, set aflame. It’s an aggressive acting out against the centralized media monopoly. Statements throughout Ant Farm’s theatrical performance reinforce this first reading. “Haven’t you ever wanted to put your foot through your television set?” asks the “Artist-President,” played by San Francisco-based artist Doug Hall doing his best John F. Kennedy impersonation. And later, Ant Farm member and “Artist-Dummy” Doug Michels says, “First the TVs go, then the freeways, then the factories.”

Clearly, Ant Farm was harnessing a generalized anti-authoritarian stance, and there was plenty of that feeling to go around, including a fevered anti-television movement and an even larger effort to rehabilitate the cultural black hole that commercial television had become. In the Bay Area itself, Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog promoted DIY independence from media saturation, Jerry Mander was hotly composing the manuscript for his controversial Five Arguments for the Elimination of Television, and the National Center for Experiments in Television, an artist-driven lab hosted by the local Public Broadcasting station, was turning the technology of TV toward abstracted imagery for meditation, an inversion of the corporate order.

Back at the parking lot, the invited audience for Media Burn, much of it the media itself, was unwittingly witnessing a publicity stunt, or what sixties theorist Daniel Boorstein would call “a pseudo-event,” an event staged to simply garner media attention. In the resulting video work known as Media Burn (and distinct from the performance), Ant Farm would incorporate their own coverage of the media coverage, creating a dizzying spiral of veracity and critique. To further drive this point home, the JFK-clone, the “Artist-President,” tells the July 4th celebrants that the ills of the nation are “militarism, monopoly, and the mass media.” The Prez goes on to declare that in its current form mass media can only “produce autocratic political forms, hierarchies, and hopeless alienation.” So how does the media apparatus digest such a discomfiting assessment? In the tape’s provided footage, local news anchors respond with homeostatic irony: “Oh, what’s it all mean? Well, presumably the message is for the media. Get it?” chortles a newscaster from KTVU-TV.

Once again, back at the parking lot: the customized 1959 Cadillac Eldorado idles on the heated asphalt while the wall of TV sets is set ablaze. The thunderous engine revs; the countdown begins. This impending collision juxtaposes two telling icons of consumerism: the automobile, that metal monster of mobility, here modified to promise lift-off as well as escape; and the TV set, that domestic outpost of corporate control, promising escape through the dream life of advertising and managed desire. The helmeted Ant Farm drivers of the “Phantom Dream Car” are there to enter “uncharted territory…as surely as Armstrong and Aldrin when they set foot on the moon,” declares the Artist-President. But the price of admission to this “territory” requires the obliteration of a principal commodity of American culture. Ultimately, Media Burn is a purification ritual, demanding the immolation of a consumerist icon, the TV set, to purge us of its suffocating hold.

Ant Farm’s prescient performance saw the end of the hegemony of American mass media, at least in its 20th Century form—the centralized control of information, the monolithic delivery, the onslaught of commodified desire. But what they couldn’t foresee was the even more virulent form that would rise from Media Burn’s ashes in which the Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), apotheosized in the tablet and smartphone, would feign a seductive intimacy, irrevocably capturing us through its purported gateway to distraction, yearning, and globalized gratification. Media Burn would not be staged today; there’d be no customized Tesla quietly speeding toward a flaming mound of iPhones. At least, not with my phone.